How long has it been since you heard the phrase “information superhighway”?

Until I just reset that clock for you, I wouldn’t be surprised if it had been going for well over a decade. From our sci-fi future world, looking back to a time before the Internet started to come into its own sometimes feels like archaeology.

In fact, the questions Indiana Jones might have asked in his more academic days about pre-agricultural Egypt would probably have been remarkably similar to questions my generation asks about the world before the Internet: Who were these people? What tools did they use? How did they see new inventions and innovations? How many died needlessly in the Cola Wars?

I admit, I was just a kid in the ’90s. I’ll give you a second to scoff and say something about how old you were then.

Done? Alright. Even though I was pretty young, I was old enough to remember the endless commercials for new versions of AOL, the free floppy disks and CD-ROMs in the mail, the now-comically large and dated laptops in movies and TV, and the phrase “information superhighway.” For a world that had only ever known knowledge to be locked up in books and people’s heads at best, the Internet really must have been an incredible idea.

These days, it’s standard. A given. Unremarkable. “Information has always been free and accessible, right?” children may ask if they could speak properly. “Were people content with not knowing things before the Internet? Before Google?”

Ah yes, our dear friend the search engine appears. A tool that was created for the sole purpose of answering your questions—questions about anything. As we know, Google especially has been the question answering vanguard. Their tools are aimed to answering your questions without having to go to another page. Perhaps eventually, you can ask your computer or phone a question—Star Trek style—and get an immediate answer.

Wait a second…we can!

But what makes this possible? How is information so free and accessible in the first place? One word:

Organization.

This is definitely an old world idea, as grumpy librarians will vociferously testify. In fact, if you want a visual of how information is organized in the Internet, go to a library. Each section may represent a topic, each shelf a sub-topic, and each book a specific thing, full of information about it. Therefore, a book in a digital library doesn’t have a subject, it is a subject.

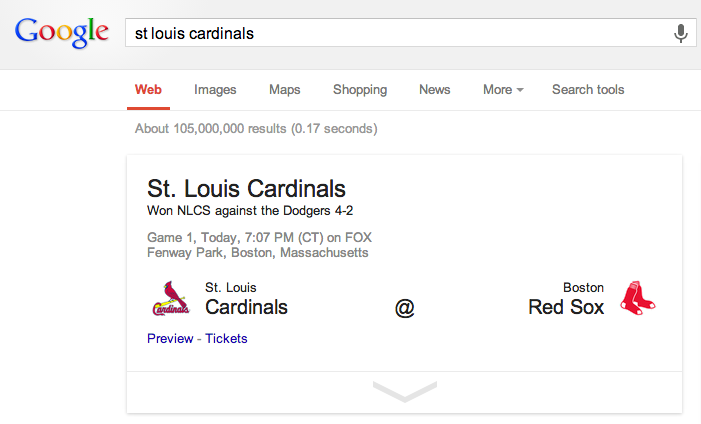

For example, try typing a noun into Google, a specific entity that will have lots of information attached to it. Say, the St. Louis Cardinals. Go Cards.

As far as Google is concerned, those 105 million results make up the “book” that is the St. Louis Cardinals: everything about or that mentions the Redbirds is somewhere in those results, in order of relevance, timeliness, influence, etc. And see that handy box to the right of the search results? That’s Google’s Knowledge Graph: a summary on the inside cover that gives you all the basics, updated in real time. This information is drawn from many places, including official sources, the CIA World Factbook, Freebase (a database of information), and Wikipedia.

But, “knowing,” to quote G.I. Joe, “is half the battle.” The other half?

Standardization.

Now before I induce the ghost of Melvil Dewey to haunt me, the standards for the way this information is organized are also critical to providing quick, accurate answers. Search engines use schema.org for this purpose, a collaborative project created by Google, Bing, and Yahoo!. That’s right. Together. Schema.org provides templates for organizing information about just about anything on websites.

Here’s an example for organizing information about a book and how to implement the code. Pretty thorough, right? By setting a standard, information can become more complete and more easily-accessible, making this whole business of searching a much smoother affair.

Now we get to the application:

Star Trek.

With Google’s latest Hummingbird update announced last month, Google is making a conscious and public effort to improve full-question searches. That is, when you ask your phone a question in your best Captain Picard voice, you’ll get the answer you want, not a misunderstanding because you asked like a human would.

The best examples for these kinds of searches are facts or calculations. Try searching in full questions for the distance from Earth to the Moon, what 2+2 equals, or what the temperature is outside, and you’ll see that you get an answer without having to look or click any further. Even to a child of the Information Age, that’s pretty rad.

With this improving capability and the importance of organization and standards to its performance, you’ll want to make sure your “book” is filled out correctly!

Whether you want to think of the Internet these days as an “information superhighway,” an “information super library,” or simply a “place to find cute pictures of cats,” it’s still looking more and more like science fiction.

So what’s next, lightsabers? Wait, really?!